| |

Back

THE

EMPIRE STRIKES BACK THE

EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

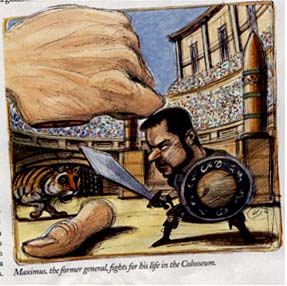

Gladiators

galore in Ridley Scott's Rome.

BY ANTHONY

LANE

The

new Ridley Scott picture "Gladiator" begins in triumphant gloom. The

date is 180 A.D., and the Roman general Maximus (Russell Crowe) is

stuck in the mud and mists of Germania, on the northern flank of the

Empire; his legions, fanatically faithful to their leader, are ranged

against a tribe of Germans so aggressively hairy that even a soldier

as war-wise as Maximus is uncertain whether to harass them with cavalry

from the rear or simply shave them to death. Maximus is followed into

battle by his fearsome dog. "At my signal, unleash hell," he says.

Is that a battle cry, or is it time for a walk? At any rate, we are

plunged into a melee of sprayed blood and breath that steams in the

air; great tubs of fire are catapulted toward the enemy, and flaming

arrows fly like shooting stars. Victory nears amid descending snow.

We have

been here before. The date was 1964 A.D., and the movie director Anthony

Mann was sticking to his guns, or his javelins, in "The Fall of the

Roman Empire." The most memorable scene in that overarching, undervalued

movie is also set on a northerly plain, with lighted torches flaring

in swirls of snow. I guess that Ridley Scott and his writers--David

Franzoni, John Logan, and William Nicholson --are trusting the short

memories of the movie going public, but I was touched to see them

returning to the embrace of so wondrous an image. It seems to gather

in all the fearful ambitions of an imperium; are we meant to imagine

civilization blazing a trail through barbarous wastes, or the scorched-earth

policies of unchecked power? Maximus himself is poised between the

two: a good man meting out brutality. Crowe is stocky, sad, and stubbled,

with a low Neanderthal brow and quick eyes, educated in suspicion;

though shorter than most of the men around him, he has mastered the

art of walking taller than any of them. Once or twice he tries a smile,

and it practically cracks the lens.

The

story is your basic three-act affair, the kind of thing that screenplay

workshops teach as holy writ. After his German victory, Maximus is

asked by the aging emperor Marcus Aurelius played by a loose haired

Richard Harris, who is about as Roman as a pint of Guinness--to be

his successor. Maximus goes away to stroke his chin and think about

it, but before he can offer a response Marcus is smothered to death

by his own son, Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix), who promptly declares

that he, not some sweaty soldier, will be taking charge. Viewers new

to the period may ask themselves how so sane and pensive a parent-Marcus

wrote the "Meditations," after all, a touchstone of the Stoic temperament--could

have sired so rich a fruitcake. Digging around, I found a fourth-century

historian who claimed that Commodus' mother fell for a gladiator and

confessed her lust to Marcus; he, in turn, ordered not only that the

gladiator should die but that his wife should wash herself from beneath

in his blood and in this state lie with her husband." That would explain

a lot. Amazingly, it doesn't get into the film.

Maximus

escapes death, goes home, finds his family slain, faints, wakes up

on a slave train, and ends up being sold to Oliver Reed. What a life.

Reed,

who plays an ex-gladiator named Proximo, died during the making of

the film--of drink, needless to say, the blood having long since passed

from his alcohol-stream. Having cowered at his Bill Sykes in "Oliver!,"

I thought he was a terrifying actor who never got his due; with his

bullock's bulk and that soft, whispering sea roar of a voice, he could

have trod the Burt Lancaster path. This last role is not quite meaty

enough for a sendoff, but I liked the sight of his blue eyes, glazed

with the tedium of daily massacre, opening a little wider as he first

watches Maximus in the ring--gold dust glinting in the sand.

All

plots lead to Rome, and Maximus, presumed dead, arrives incognito

at the gates of the Colosseum, accompanied by his new best friend

and fellow-slave Juba (Djimon Hounsou), plus a barrel load of computer-graphic

imagery.

Gladiator

takes C.G.I. about as far as it will currently go; much of the ancient

city is a virtual re-creation, as is most of the throng that packs

in to watch the games. It's hard to pin down, but your senses are

never quite pricked with the sharpness of the real; you can see the

air humming with bloodlust, but you can't smell it. Maybe that's a

good thing, because if "Gladiator" were any more authentic the audience

in the movie theatre might start spearing one another in the throat.

You

find yourself thrilling to acts of violence, but that, I guess, is

the freakish strength of this picture. It shows you the tantalizing

laws of cruelty, and it forces you to ask yourself just how speedily

you, too, would slide from citizen to lout. At one point, Russell

Crowe crosses his forearms in front of him, with a blade in each fist;

then, with a swift, double backhand jerk, he scissors a man's head

off. My, how we cheered. If Jerry Springer ran the Super Bowl, this

is how it would end up.

At the

climax, Maximus even takes on Commodus himself; this may sound unlikely,

but the young emperor was, indeed, a crazed amateur gladiator, who

fought more than seven hundred times, once against an unarmed giraffe.

So says Gibbon, at any rate, and if you want to prep yourself for

this film skim through Volume I of "Decline and Fall of the Roman

Empire." Note, in particular, the famous claim: "If a man were called

to fur the period in the history of the world during which the condition

of the human race was most happy and prosperous, he would, without

hesitation, name that which elapsed from the death of Domitian to

the accession of Commodus."

In other

words, Ridley Scott's movie-like Anthony Mann's, which had the same

background, and most of the same characters--is positioned at the

exact moment of paradise lost. "So much," says Marcus, with a weary

pause, "for the glory of Rome." It's a wonderful line: is he dissing

the fatherland or proudly recalling all the wars he has fought? 'so

much'-in the name of Pax Romana?

The

exhausted opening of the film already feels like an ending, and, with

mad gaze and milk-white armor Joaquin Phoenix, who has fleshed out

alarmingly since his gawky teens, is just the kind of bad angel who

can ruin your peace and call it entertainment. Romans rise ecstatically

to their feet, not knowing that he has brought them to their knees.

High

politics wind through "Gladiator" in a tangle of constitutional announcements.

"There was a dream that was Rome," we are told, and the echo of Dr.

King bounces awkwardly off the sight of Juba, a near-naked black man,

scrapping for the pleasure of the crowd. "Give power back to the people,"

Marcus tells Maximus, but nothing that ensues does much honor to popular

virtue, and when Maximus complains to Commodus' elegant sister Lucilla

(Connie Nielsen) that he has "the power only to amuse a mob" she replies

curtly, "That is power."

Maximus

does not want to fight, but only by fighting can he avenge his family

and salve the wounded state of Rome; on the other hand, he does rather

enjoy himself out there, wearing a spiffy helmet, engaging hungry

tigers in hand-to-paw combat, and making the charioteers wish they

had fitted the optional airbag.

"Gladiator,"

like its hero, is aroused by everything that it knows to be corrupt;

why else would the musical score (by Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard)

march so doomily in the footsteps of Mars from Hoist's "The Planets"?

"I will give the people the greatest vision of their lives," Commodus

says, and it is no accident that he sounds like a film director: D.

W. Griffith, perhaps, or Leni Riefenstahl, one of those dangerous

geniuses who remind you what menace a vision can bear.

There

are times when "Gladiator" appears to be not so much photographed

as cast in iron: gray-blue skies, flesh as cold and colorless as the

armor that protects it, and hardened profiles that you could stamp

on a coin. I spent half the movie trying to work out what the computerized

Rome reminded me of, and then I clicked; it was Albert Speer's designs

for the great Berlin of the future. Scott's is hardly a Fascist film,

but it is insanely watchable in ways that set you fretting; like his

own "Blade Runner," it makes you desperate to know the worst--to see

what extremes this poisoned world can stretch to. When one gladiator

has another pinned on the ground like an insect, he asks the Emperor

to decide the fallen man's fate by the raising or lowering of a thumb.

The mob does its best to sway his choice, which leaves us with the

disconcerting spectacle of multiple, raving, Latin-speaking Siskels

and Eberts-forty thousand thumbs way down.

So that's

what mass slaughter was like: just another trip to the movies.

|