CLIVE OWEN’S latest film was directed by that master of moodiness, Wong Kar-wai, and lasts all of 20 seconds. In a commercial for Lancôme’s new men’s fragrance — shown on television outside Britain and the United States but easily found online — he strides down a hall, a suggestive expression on his face, to embrace a beautiful woman. That’s it. Yet this stylized minifilm captures some elemental aspects of his career.

There is, obviously, the movie-star handsomeness. But there is also his pattern of working with top directors, and above all his minimalist acting style: so much emotion on his face, so little visible movement. That subtle approach, nuanced so the slightest glance registers with the camera, has shaped his finest, deepest work: in 2004 as a jealous, manipulative doctor in Mike Nichols’s “Closer” (he got an Oscar nomination for that), and last year as the disaffected alcoholic who helps save the human race in Alfonso Cuarón’s visionary “Children of Men.”

And arriving almost back to back, his two new full-length films create a moment that highlights his immense versatility.

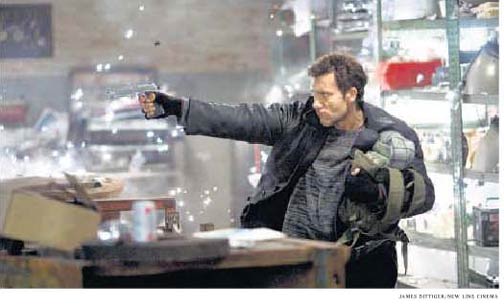

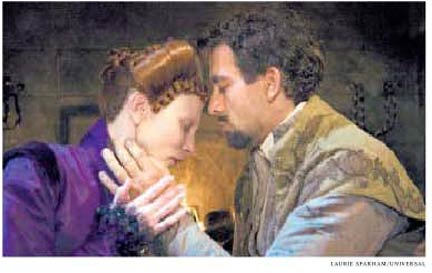

“Shoot ’Em Up” (opening Friday) begins with an image found in several of his movies, as well as the Lancôme spot: an extreme close-up of his eyes, shrewdly hinting at surprises to come. Here the camera pulls back and reveals him to be a rumpled guy sitting on a bench munching a carrot, which he soon uses as a lethal weapon, stabbing a villain through the throat. And if a cartoonish action movie can find a way to exploit his looks, how much easier for “Elizabeth: The Golden Age” (opening Oct. 12), in which he plays a seductive Walter Raleigh opposite Cate Blanchett as the middle-aged Elizabeth I. Wrenching a line furiously out of context, the film’s trailer has her take one look at him and say, “Well, well” in a way suggesting that it’s Elizabethan for “Ooh-la-la.”

We met in a downtown cafe when he was in New York a few weeks ago. His greenish eyes are wider than they seem on screen, as if he is perpetually surprised; he talks fast, in a casual, friendly way. But one quality sets him apart from most actors and offers a clue to his minimalist approach: He does not need to charm everyone who crosses his path, just as he does not need his characters to be loved on screen.

“The worst piece of advice I was ever given by somebody, a long, long time ago, was ‘Clive, it’s all about likability,’ ” he said. Who advised that? “I’m not telling,” he laughed, but “I remember going, what a ridiculous thing to say about acting.”

Even now, “I’m fearless about that,” he said. “I don’t go into my parts wanting the audience to like me. I’m much more interested that they understand and believe me.”

His fierce refusal to play the likability game is a huge asset artistically. Even his heroic characters have the depths and shadows of real men. And without an easily pegged persona, he carries little baggage to the screen. If Tom Hanks is the Nice Guy and Jack Nicholson the Devilish Guy, Clive Owen is whatever guy he happens to play.

But that slightly chilly relationship with the public may also account for the one thing missing from his career: a megahit, a “Bourne”-size franchise to call his own. In last year’s remake of “The Pink Panther” he even had a cameo mocking rumors that he was in line to be the new James Bond. Steve Martin, as Inspector Clouseau, walks into a casino where Mr. Owen, urbane in a tuxedo, introduces himself: “Boswell. Nigel Boswell,” he says. “Agent 006. Know what that means?”

“ ’Course I do,” says Clouseau. “You are one short of the big time.” (Mr. Owen has always said he was never approached for Bond.)

“Shoot ’Em Up,” the first splashy action movie he has had to carry, is decidedly un-Bond-like, a grittier, more youthful film. His character, known only as Smith, delivers a baby in the middle of a shootout and, with the help of a breast-feeding prostitute, protects the boy from killers. This is not the career choice of someone calculating the next big thing at the multiplex.

“Shoot ’Em Up,” the first splashy action movie he has had to carry, is decidedly un-Bond-like, a grittier, more youthful film. His character, known only as Smith, delivers a baby in the middle of a shootout and, with the help of a breast-feeding prostitute, protects the boy from killers. This is not the career choice of someone calculating the next big thing at the multiplex.

The Looney Tunes carrot sets the tone for violence that is playfully over the top, yet Mr. Owen portrays Smith with utter realism. “I wouldn’t have liked to have done that film nodding all the time, saying, ‘It is ridiculous, you see, it’s ridiculous,’ ” he said. “I have always thought cinema audiences are pretty sophisticated,” and the heart of screen acting is “communicating something as economically and concisely as you can.”

Michael Davis, the film’s writer and director, said: “He would come to me and say: ‘You don’t have to have the character say so much. You’re going to see it on my face. Why don’t you change these three sentences to these three words?’ ”

“The Golden Age” proves he can play a traditionally dashing romantic hero: in a central scene Raleigh tells Elizabeth about discovering land, describing his adventure in veiled sexual terms. But “Shoot ’Em Up” seems more typical: it comes from the part of him drawn to thornier types.

He gives what may be his most moving performance as one of those unheroic heroes in “Children of Men.” His character, Theo, is a onetime idealist recruited to help the first woman to become pregnant in 18 years escape groups trying to exploit her.

“I usually have a very strong instinct when I read a script,” he said. “I really wasn’t sure about doing that film because the character is so apathetic. You’re playing somebody who’s depressed and cynical and so reluctant.” He continued, “I just wasn’t sure I saw my way into that.” Even now he can only say, “I felt very strongly that there just had to be an overwhelming sadness about the guy.”

He is clearly better at acting than at dissecting how he does it, and Mr. Cuarón laughed knowingly when told that his star was vague when talking about their process. “The thing you have to know about Clive is that he’s not an intellectual in the way he approaches his character,” he said by phone. “He’s completely instinctual. He may analyze the thing later and say, ‘I understand why he does that.’ ”

Mr. Cuarón can describe the subtlety of the performance, though. “He knew there was a physical heaviness to the character reflecting the spiritual heaviness,” he said. At the start, “his shoulders are completely dropped, and every single muscle of his face is as if it were absolutely without gravity. As he’s recovering his faith, the muscles in his face get stronger.”

“Children of Men” was disastrous at the box office, but Mr. Owen shrugs off flops as well as fame. His early success taught him how fraught stardom can be. In 1990 he was the lead in a still-entertaining television series, “Chancer” (never shown in the United States and just released here on DVD), playing an ambitious, shady former banker. In Britain he became what George Clooney was to “ER.”

Every actor has his standard life story, and the Clive Owen saga became well known in Britain then. Nearly 43 now, he comes from the working-class town of Coventry, one of five brothers reared by his mother and stepfather. At about 12 he was the Artful Dodger in a school production of “Oliver!” and knew instantly, unshakably — with the same unanalyzed instinct he brings to his roles — that he wanted to be an actor.

Just a few years out of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts he got “Chancer.” The tabloid press came sniffing around and tracked down his father, who had left the family when Clive was 3 and hadn’t seen him since. “I was naïve, and they threw every kind of tabloid newspaper into my trailer,” he said of the reporters. “I didn’t realize you could say no, you could be discerning about who you spoke to. So anybody could come and grill me about my family. It just wasn’t very pleasant.”

Looking back, “I never understand anybody that sits there and talks about the really important things in their lives in the media like that,” he said. “And so it just made me protective.”

By 1998 and his American breakthrough in the independent film “Croupier,” he had figured out how to guard the line between the private and the public Clive. A dozen years ago he married Sarah-Jane Fenton, who had played Juliet to his Romeo on tour with the Young Vic. He shields their daughters, now 10 and 8, from the spotlight and the paparazzi with un-Hollywood-style common sense. “You just don’t take them to places where you’re obviously going to be photographed,” he said.

That may help explain why the lack of megastardom doesn’t bother him. “There’s no part of me that is hankering for, that feels the need for that,” he said. Well, what else would someone in his position say?

Patrick Marber, who wrote the theater and film versions of “Closer” and directed Mr. Owen in it on the London stage, said, “Like any actor, I’m sure he’d love to be a big box-office success.” But he added: “He’s genetically incapable of spending three months making a movie that he thinks is rubbish, and some actors can do that cheerfully. It’s not because he’s so moral, but he’d hate himself, and it would bore him.”

Becoming the male face of Lancôme isn’t the move of someone snobbish about his art, but didn’t anyone suggest it might not be the best career maneuver? “No,” Mr. Owen said, seeming amused at the idea, “no one did.” (Of course arty commercials have been good to him; in 2000 “The Hire,” a groundbreaking online series of short films for BMW, paired him with directors like Ang Lee and John Woo.)

However ambivalent he may be about fame, he is the undisputed star of his next films: a political thriller directed by Tom Tykwer (“Run, Lola, Run”), “The International,” and a drama about a widower with two sons, “The Boys Are Back in Town,” for Scott Hicks (“Shine”). And he has taken control of a project with the potential to become his franchise: he is executive producer and will star as Philip Marlowe in “Trouble Is My Business,” based on a 1939 Raymond Chandler story. He chose a Chandler piece that hadn’t been filmed before, he said, because “the last thing I need is to be compared to Humphrey Bogart.”

Or maybe that absence of the typical actor’s craving to be loved means he’ll never get the blockbuster. Chatting about Robert Altman, who directed him in “Gosford Park,” he said: “Altman told me that he never wooed an actor. He’d talk to them, and if they needed a bit of wooing, he’d have to back off, because he was never going to promise them things that he couldn’t deliver.”

That anecdote seems to reflect something fundamental to his career, so a week later on the phone I asked about it and his uningratiating screen style. “It’s fundamental only in the way that people ultimately respect honesty more than they do charm,” he said, which sounds direct but may be slyer than it seems. Because, on second thought, that comment is quite charming in its honesty.