|

|||

|

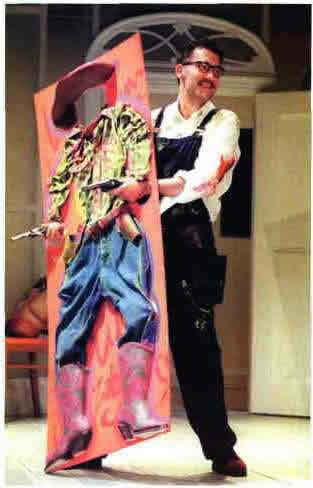

From Marg: "I

have just gone thru the experience of theatre as it should be presented.A

wonderful thing to behold as you well know! Mr.Owen covered every

emotion,

a true craftsman. I will email more details later.I am sending a card

today to the theatre on all of our behalf.I hope this meets with

your

approval. I also thought it might be a nice gesture to send flowers

on Saturday as a send off. The

theatre was packed.There were people from all parts of the globe. Some

were only conversant in their own language.The atmosphere was electric,diffused

slightly by the fact that the revolving stage failed to revolve and

had to be shifted manually! Much clapping and cheering followed that!

Clive felt his way around the audience and the opening scene was

a temperature

gauge I'm sure. It set us back on our heels and we were won over from

the onset. He was enjoying himself and was determined we would do

the

same - and we did! I will write more later but must sign off now." |

|||

|

Accidentally, perhaps, Nichols's play shows that we have come a long way in the past 34 years. Thank goodness for women's employment, cheap telephones, and for the much more ready resort to Caesarean surgery to deliver the foetus in distress. After the assured clarity of the play's first half, the second seems more confused, and has a few touches of "White Christmas" corniness. Yet there is no decline in the standard of acting. John Warnaby as Freddie, for instance, gives a marvellously convincing rendition of the bossy liberal who can't bear to leave a social problem unsolved by himself. But Nichols's points become more laboured, and both Robin Weaver as Pam and Prunella Scales as Bri's smothering mother, Grace, have to work hard to rise above caricature. They succeed, however, and this must rank overall as one of the best stage productions of 2001.

|

|||

|

IN THE

programme notes, Peter Nichols writes apologetically about the blackish

comedies that have followed where his Joe Egg led. The blind, deaf-mutes,

sterility, mastectomy, cancer: "every handicap has its hilarious

smash hit, each with its hard jokes and soft centre, sucking up to its

public in the approved style of funny boo-hoo." Well, I have yet

to see a laugh-riot about mastectomy; but, even if it exists, Nichols

should not feel too responsible. Even an uncertain revival, such as

this, shows that Joe Egg, far from being sentimental and ingratiating,

is a play that makes you think while you feel and feel while you think,

in each case about a subject of major concern. If anything, it is of more concern than in 1967, when amniocentesis did not exist, abortion was mostly confined to the back streets, doctors found it harder indefinitely to prolong life, and euthanasia was, happily, not on the European agenda. What should be done for and with such as Jo, Brian and Sheila's profoundly damaged child? Were Nichols writing about her today, I suspect he would introduce more science into the dramatic equation. But his play still seems impressively complete, looking as it does at a "human vegetable" in terms of metaphysics, nappy-changing and plenty in between. Moreover, it does so without venturing out of Bri and Sheila's troubled living room. He wants Jo in a home, she won't hear of it. He has renounced all hope of improvement, she clings to the memory of the day, nine years ago, when Jo summoned up the intelligence to knock over a pile of coloured bricks. She regards him, rightly, as immature; he sees her, also rightly, as unrealistic. Either way, they mask their feelings by pretending that the figure sightlessly slumped in her wheelchair is the sort of wayward, demanding daughter everybody else seems to have. It gradually becomes clear that Jo is keeping them together yet driving them apart. Clive Owen, a nervous, driven Bri, and Elizabeth Garvie, an earnest, responsible Sheila, missed too much of the pain on opening night. Even when the games and the jokes stopped, and she started remembering those toy bricks, the emotional temperature stayed several degrees lower than the literal one on what was, admittedly, a hideously steamy evening. But they kept the play banging entertainingly along, whether they were spoofing inept doctor or glacial consultants for the benefit of the audience, or coping with visitors who ran the gamut of insensitivity. Here is the play's weakness. Most friends would be less unsubtle than Freddie, the smug do-gooder who wants Jo institutionalised, or his wife Pam, the genteel Hitlerite who would happily see her killed for research purposes. And if each of them too obviously represents an attitude Nichols thinks we should hear, Bri's mum has no reason for venturing into the living room except to bait the self-doubting Sheila by combatively infantilising her husband. Yet despite that, despite the inadequacies of Lisa Forrell's cast, Joe Egg is clearly a modern classic, and would merit a major revival. If you doubt its pull, watch Katey Kastin's frail Jo embodying her mother's fantasies by suddenly skipping and singing across the stage, like any ten-year-old Jane or Jill. Is there a more touching moment in contemporary drama? I don't know it. Reviews above thanks to Erica |

comedy to carry us down the deepest abysses of human suffering. But

Peter Nichols's explicit echoes of Lear's request, first for a mirror,

then for a feather, to test whether the comatose child breathes, does

not depend in the least on Shakespearean allusion for its heart-rending

effect. Nichols's play is genuinely original.

comedy to carry us down the deepest abysses of human suffering. But

Peter Nichols's explicit echoes of Lear's request, first for a mirror,

then for a feather, to test whether the comatose child breathes, does

not depend in the least on Shakespearean allusion for its heart-rending

effect. Nichols's play is genuinely original.