|

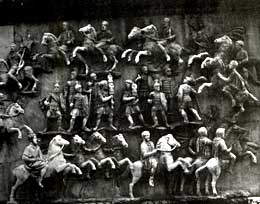

The barbarians

began to beat upon the walls of the empire as early as AD 160....they

came on horseback, bringing new tactics for the Roman infantry to face,

and they came in masses. We may doubt if any military sustem could have

permanently stayed this series of human tides. But the Empire did what

it could....

From the

Brittanica |

The

Roman Army

In

the Roman army, the commanding officer of a legion was called the Legate.

He was assisted by a deputy called the Camp

Prefect, and a staff of six senior administrative officers called Tribunes.

The original function of the Tribunes was to spread the call to arms and

to ensure that the citizens rallied to the Eagles in time to march and

fight. Later, the Tribunate became more of a political tenure, a training

ground for young noblemen waiting to go into the consular or civil services.

Whenever a Tribune chose to distinguish himself militarily rather than

serve his time administratively and get out, his success was almost preordained.

There

were normally 28 legions in commission at any given time, and each legion

was divided into 10 cohorts. By the end of the third century, the first

two cohorts of each legion had been expanded to Millarian status, which

meant that each held 1,000 men and was the approximate equivalent of the

modern  battalion.

Prior to that time, only the First Cohort had been Millarian. To the First

and Second Cohorts fell the honor of holding the right of the legion's

line of battle, and they were made up of the finest and strongest battle-hardened

veterans. Cohorts Three through Ten were standard cohorts of 500 to 600

men. Each Millarian cohort was composed of ten maniples, and a maniple

was made up of ten squads of 10 to 12 men each. battalion.

Prior to that time, only the First Cohort had been Millarian. To the First

and Second Cohorts fell the honor of holding the right of the legion's

line of battle, and they were made up of the finest and strongest battle-hardened

veterans. Cohorts Three through Ten were standard cohorts of 500 to 600

men. Each Millarian cohort was composed of ten maniples, and a maniple

was made up of ten squads of 10 to 12 men each.

The

bulk of the legion's command was provided by the Centuriate, from the

ranks of which came the centurions, all the middle-and lower-ranking commissioned

officers of the legion. There were six centurions to each cohort from

Three to Ten, making 48, and five senior centurions called primi ordines,

in each of the two Millarian Cohorts. Each legion had a primus pilus,

the senior centurion, a kind of super- charged Regimental Sergeant Major.

The primus pilus headed the First Cohort, the Second Cohort was headed

by the princeps secundus, and Cohorts Three through Ten were each commanded

by a pilus prior. The Roman centurion was distinguished by his uniform:

his armor was silvered, he wore his sword on his left side rather than

his right, and the crest of his helmet was turned so that it went sideways

across his helmet like a halo.

ranks of which came the centurions, all the middle-and lower-ranking commissioned

officers of the legion. There were six centurions to each cohort from

Three to Ten, making 48, and five senior centurions called primi ordines,

in each of the two Millarian Cohorts. Each legion had a primus pilus,

the senior centurion, a kind of super- charged Regimental Sergeant Major.

The primus pilus headed the First Cohort, the Second Cohort was headed

by the princeps secundus, and Cohorts Three through Ten were each commanded

by a pilus prior. The Roman centurion was distinguished by his uniform:

his armor was silvered, he wore his sword on his left side rather than

his right, and the crest of his helmet was turned so that it went sideways

across his helmet like a halo.

Each

centurion had the right, or the option, to appoint a second-in-command

for himself, and these men, the equivalents of non-commissioned officers,

were known for that reason as optios. Other junior officers were the standard

bearers, one of whom, the aquilifer bore the Eagle of the legion. There

was also a signifier for each century, who bore the unit's identity crest

and acted as its banker. Each

centurion had the right, or the option, to appoint a second-in-command

for himself, and these men, the equivalents of non-commissioned officers,

were known for that reason as optios. Other junior officers were the standard

bearers, one of whom, the aquilifer bore the Eagle of the legion. There

was also a signifier for each century, who bore the unit's identity crest

and acted as its banker.

Each

legion also had a full complement of physicians and surgeons, veterinarians,

quartermasters and clerks, trumpeters, guard commanders, intelligence

officers, torturers and executioners.

The

Roman Cavalry

By

the end of the second century AD, cavalry was playing an important role

in legionary tactics and represented up to one-fifth of overall forces

in many military actions. Nevertheless, until the turn of the fifth century,

the cavalry was the army's weakest link. The Romans themselves were never

great horsemen, and Roman cavalry was seldom truly Roman. They preferred to

leave the cavalry to their allies and subject nations, so that history

tells us of the magnificent German mixed cavalry that Julius Caesar admired,

and which gave raise to cohortes equitates, the mixed cohorts of cavalry

and infantry used in the first, second and third centuries AD. Roman writers

also mention with admiration the light horsemen of North Africa, who rode

without bridles.

horsemen, and Roman cavalry was seldom truly Roman. They preferred to

leave the cavalry to their allies and subject nations, so that history

tells us of the magnificent German mixed cavalry that Julius Caesar admired,

and which gave raise to cohortes equitates, the mixed cohorts of cavalry

and infantry used in the first, second and third centuries AD. Roman writers

also mention with admiration the light horsemen of North Africa, who rode

without bridles.

Fundamentally,

with very few exceptions, cavalry was used as light skirmishing troops,

mainly mounted archers whose job was patrol, reconnaissance and the provision

of a mobile defensive screen while the legion was massing in battle array.

Roman cavalry of the early and middle Empire was organized in alae, units

of 500 to 1,000 men divided into squadrons, or turmae, of 30 or 40 horsemen

under the command of decurions. We know that the Romans used a kind of

saddle, with four saddle horns for anchoring baggage, but they had no

knowledge of stirrups, although they did use spurs. They also used horseshoes

and snaffle bits, and some of their horses wore armored cataphractus blankets

of bronze scales, although there is little evidence that this form of

armor, or armored cavalry, was ever widely used.

Until

the fifth century, and the aftermath of the Battle of Adrianople, it would

seem that almost no attempt had been made to study the heavy cavalry techniques

used in the second century BC by Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander

the Great. It was that renaissance, allied with the arrival of stirrups

in Europe somewhere in the first half of the fifth century, that changed

warfare forever. In terms of military impact, the significance of the

saddle with stirrups was probably greater that the invention of tank.

|